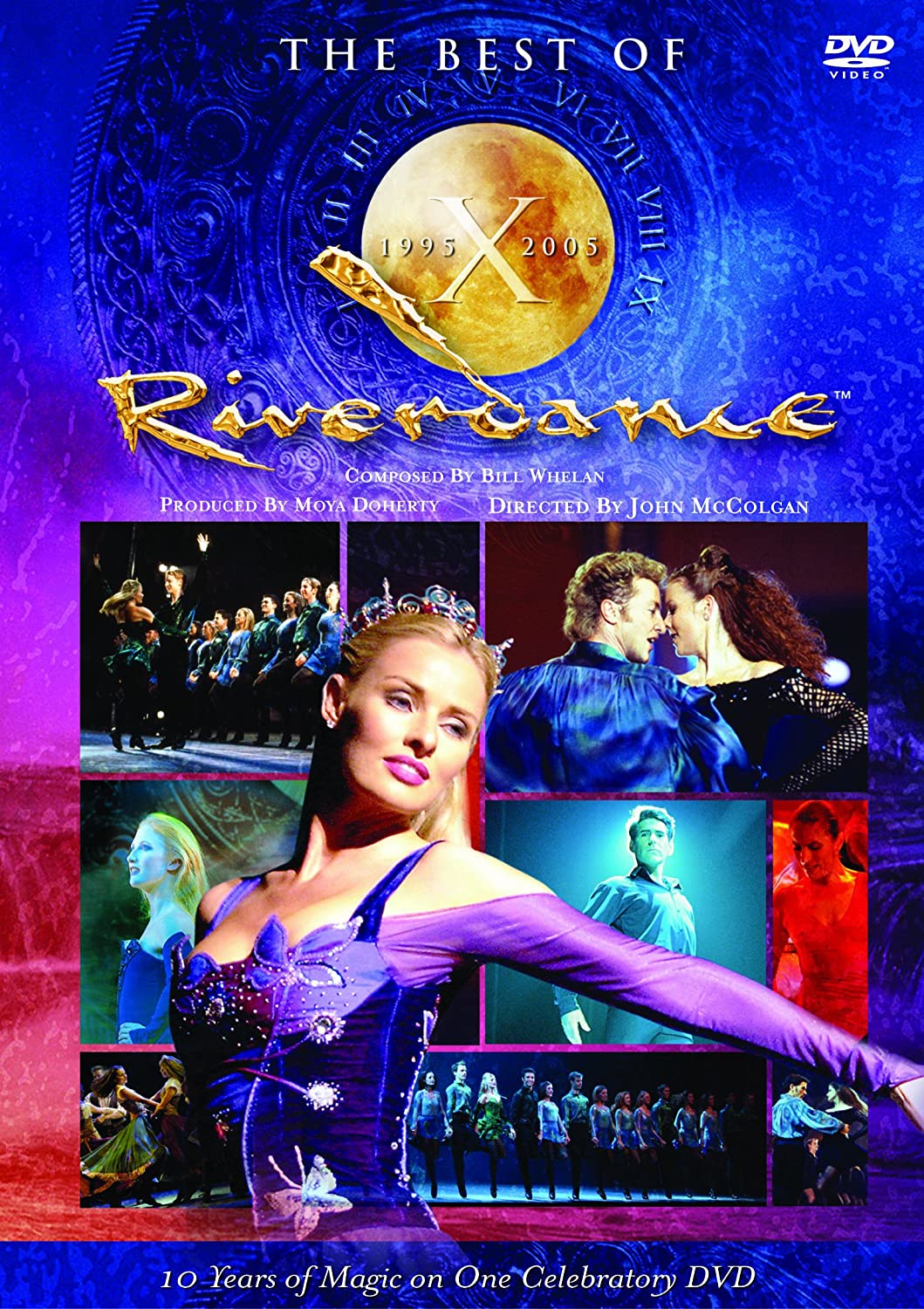

Click the image to watch the original, 1994 performance! Click the image to watch the original, 1994 performance! Riverdance Now that we’ve reached modern times in our origins series, it’s impossible not to mention Riverdance. If you were around in the 90s or early 2000s, chances are it’s how you heard about Irish dance in the first place. Riverdance was a global phenomenon that’s still considered one of the most successful dance performances of all time, grossing, by its 20-year reunion, over a billion dollars worldwide. And while the most traditional aspects of Irish dance live on, it would be impossible to deny the new life and interest that Riverdance helped breathe into the time-honored artistic sport that is Irish dance. It all began in 1981, when composer Bill Whelan was asked to write and produce an interval act for the Eurovision Song contest (which is now something like a pan-European X-Factor, but all music-based, and at the time was considered a very serious music competition.) This first piece was called “Timedance,” and featured Irish folk group Planxty playing baroque-inspired music with ballet dancers accompanying. When Bill Whelan was approached again (with 7 wins, Ireland has won the Eurovision contest more than any other country) in 1994, he decided to do something closer to Ireland’s roots. He created the most successful interval show in Eurovision history, “Riverdance”—a score filled with traditional Irish instruments like drum and fiddle, paired with “haunting vocals” and, of course, Irish dancers, all with a modern twist!  Click the image to watch the 1996 touring company in NYC perform “Reel Around the Sun” Click the image to watch the 1996 touring company in NYC perform “Reel Around the Sun” People around the world (the performance was initially seen by 300 million people worldwide) were stunned and amazed by this seven-minute introduction to traditional Irish dance and music, which up to this point was only well known in Ireland and areas with high populations of Irish immigrants. The audio recording stayed at the top of the Irish singles chart for 18 consecutive weeks (it’s still the second best-selling single in Irish history, only following Elton John’s “Candle in the Wind”) and a repeat presentation was held at the Royal Variety Performance (a yearly charity event held by the British royal family) that year. Husband-wife production team Moya Doherty and John McColgan saw the opportunity for this short performance to become a full-length theatrical event, and within six months Riverdance, the show, had its first performance in Dublin. Gathering together the music stylings of Bill Whelan and choral group Anúna with choreography largely by American-born Irish dance champions Michael Flatley (yes, the “Lord of the Dance”) and Jean Butler, Riverdance was not only an immediate, but a consistent hit. The opening night didn’t just sell out, but the first five weeks at the Point Theatre in Dublin, as well as a four-week run at London’s Apollo (and a second run, which was extended twice--over 120,000 tickets initially), as well as every date at New York’s Radio City Music Hall. The original production of the show would run for 11 years, but additional tours stretched the longevity to 23 at 515 venues in 47 countries on six continents! But Riverdance wasn’t just your grandmother’s Irish dance—it combined new, sleeker costuming (no elaborate, heavy dresses with Celtic designs or high-bouncing curls) with influences from other dance traditions, expanding the insular world of Irish dance for the world stage. While it made use of Irish dance’s iconic forms and steps, it also used choreographed arm movements and emotional ebullience to complete the performance, instead of the traditional stiff upper body and relatively controlled expressions. Drawing from other cultural dance traditions, such as flamenco and tap, Riverdance placed Irish dance as part of world dance tradition rather than completely apart (and engaged the audience in new, theatrical ways not entirely reliant on technique, as is all-important in the world of competitive Irish dance, as well!) The producers likened Riverdance as a mirror to the cultural revolutions happening in Ireland and throughout the world. Ireland of the 1990s was embroiled in the Troubles and Riverdance became a symbolic representation of the way Irish society was changing.

Little known to the casual Riverdance-enthusiast, Flatley actually wasn’t in the show for long. While he and Jean Butler were the stars of and choreographed the original, Eurovision performance, Flatley left the theatrical show only a few months after it originally premiered. There appears to not be one reason he left, but many—Flatley’s desire for complete creative control, his refusal to sign a contract over profit-sharing, salary, and royalty disputes, or, according to Jean Butler: his own ego. (Click that link for Butler’s more detailed description of working with Flatley—it’s an interesting read!) Flatley’s lawsuit against the production wasn’t settled until 1999, but it didn’t stop Flatley from garnering international acclaim from his own spin-off shows, Lord of the Dance and Feet of Flames among them. Flatley even holds the title of “Highest Paid Dancer” in history in the Guinness Book of World Records. While Riverdance might not be exactly the traditional Irish dance we teach at SRL, its influence lives on and had the positive affect of making Irish dance a household name worldwide. The show opened this once narrow cultural practice to those outside of Ireland, revived interest within its home country, and no one can deny—it’s quite a show! If you’re ever able to catch a performance don’t hesitate--the 25th anniversary show is even touring now! This post is part of a series. Read our last origins of Irish dance post, all about sean-nós, here. Check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram.

0 Comments

Sean-nós Dance In our Origins of Irish Dance series, we’ve covered everything from Irish dance’s druidic origins and 18th century dancing masters to competitive levels and modern costuming. However, there’s something we breezed right past, as it’s a deviation from the standard Irish step we teach at SRL: sean-nós dance! (Though we have dabbled in sean-nós before with dances like Maggie Pickens and a summer masterclass with guest instructor Annabelle Bugay!) Tonight, we’re taking a step back to take a look at this branch of Irish dance tradition that has had wide-reaching influence on not only Irish step dance, but other forms of dance as well. Sean-nós, meaning “old-style,” is a solo, percussive, usually improvised style of Irish dance strongly associated with Connemara on the west coast of Ireland. Unlike Irish step dance like we teach at SRL, which is highly regulated by the CLRG in Ireland, sean-nós is a more casual dance form that predates any modern records and developed differently in disperse areas over time. Sean-nós dancers, due to the improvisational nature of the dance that favors personal style over precision, normally dance alone, though many often take turns dancing to the music. Generally danced in a social setting, like a pub, party, or cultural festival (though competitions now exist, as well as some “standard” steps!), this form of Irish dance is more stripped down than step in both presentation and musical choices. While Irish step dancers perform highly choreographed routines in often elaborate costumes with stiff arms and high kicks, sean-nós Irish dancers throughout time have tended to favor their street clothes, improvised steps, free arm movement, and footwork that stays low to the ground. Additionally, while adjudicators expect a competitive step dancer to move over the entire stage during a performance, sean-nós was traditionally performed in tight spaces: a door taken off its hinges, on a tabletop, or even on the top of a barrel! There was even an old saying about how a good dancer could perform on a silver serving tray, but a great dancer could perform on a sixpence. (Though sean-nós dancers these days generally just prefer a hardwood floor.) Then, there’s the shoes. While any Irish dancer knows all about ghillies and hard shoes (check out a history of Irish step shoes here,) sean-nós dancers don’t have a particular type of shoe they’re tied to. However, they are looking for something that can make some noise! Sean-nós concentrates on what they call the “batter” i.e. hard, percussive sounds that emphasis the accented beats in the usually 8-count music being played as they dance. Many modern sean-nós dancers actually prefer tap shoes! While Irish step hard shoe and sean-nós have has much in common as they do differences by way of proximity, sean-nós also made a huge impact on the world of American dance forms. With the influx of Irish immigrants in the 1800s during the Great Famine, sean-nós made its way to the U.S. and subsequently became a part of our culture, whether we realized it or not! While sean-nós itself isn’t widely found in America modern day, it highly influenced the vaudeville era of American dance, lending its style to soft shoe, flat-footing, hoofing, and clogging—all precursors to American jazz and tap!

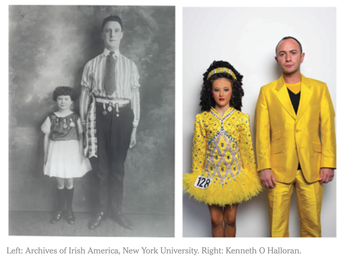

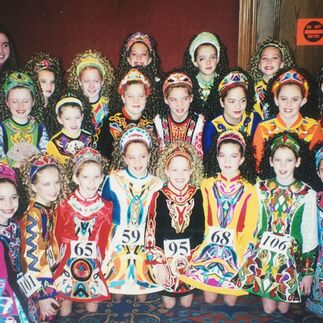

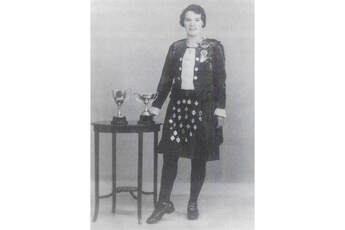

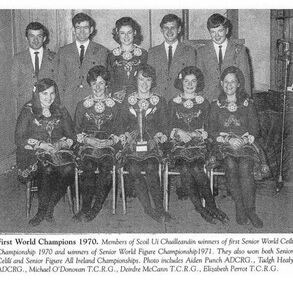

So, while SRL may not have a sean-nós class, this old-style of dance is still an intrinsic part of the story of Irish dance’s (and American dance’s) history. And it still lives on in many a pub and party today. (Can’t forget a pretty epic flash mob in Galway in 2013 to promote the 116th Oireachtas Festival there! Watch a video of it here.) This post is part of a series. Take a look at our last “Origins of Irish Dance” post, all about modern male costuming, here. Also: check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram.  The early 1990s versus the early 2000s The early 1990s versus the early 2000s The Look, Part 4: Male Costuming Fashion, in or out of the dance world, has long been a female-dominated realm. However, while that means male Irish dancers have had significantly less changes over the years, they haven’t completely escaped the glamification of their costumes! Today we’ll take a look at that evolution and how our current expectation for male Irish dance costuming came to be.  Kilts were worn commonly into the 90s, especially as school costumes Kilts were worn commonly into the 90s, especially as school costumes While we know from our first installment (catch up here) that most Irish dancers started by dancing in their regular clothes, men’s costuming actually appears to predate women’s. Dance masters were typically male, and as they often dressed flamboyantly to help drive business, they were known by their fancy hats, swallowtail coats, breeches, white stockings/socks, and shiny, silver-buckled shoes. Due to British rules and restrictions (the impact of which was felt for 100s for years,) most male dancers simply wore their “Sunday Best” as their female counterparts did—typically a shirt and tie with breeches tucked into knee socks, a cummerbund around the waist. Similarly to female trends, as time passed there was a focus on traditional Irish fabrics and designs. For instance, in 1904, at the first Glens Feis in Glenarriff, Co. Antrim, the first prize for one of the competitions was: “a suit of Irish Homespun, presented by Hamilton and Co. Portrush, Co. Antrim.” While kilts as a male clothing item is associated in our modern minds with Scotland, Irish dance has always been about the feet, so kilts became a typical item dancers (male and female!) wore for many years (largely from the 1910s to the 1960s.) Pipers first wore them, but as Irish dance and music are completely intertwined, the dancers eventually adopted the look at well. (If you check our previous post about Irish dance shoes, you’ll find Ireland and Scotland are intertwined in many aspects of their dance traditions!) Kilts were typically worn with a short coat and brat/cape (the male version a bit shorter and usually attached to the front of the coat with a Celtic design brooch—they’re a holdover from times of rebellion,) along with shirt, tie, and knee socks. These days, boys still have the option to wear a kilt, but since premiere of Riverdance in 1994, pants have gradually become the norm. Male dancers typically wear long (black) pants (though very young dancers sometimes perform in short pants,) a shirt, and often a vest and tie. For many years, it was a trend for male dancers to emulate the sparkling, bright dresses of the female solo dancers through their vests and ties. However, in recent times there’s been a movement toward more sleek, sophisticated looks rather than full on sparkle all the time!  The Gardiner Brothers’ viral tiktoks have influenced a more cool, casual look for male Irish dancers in the last few years (doesn’t hurt they have 5 World Championships between them!) The Gardiner Brothers’ viral tiktoks have influenced a more cool, casual look for male Irish dancers in the last few years (doesn’t hurt they have 5 World Championships between them!) And that’s a wrap on our series all about the whys and hows of Irish dance’s iconic look came to be! One of the most exciting things about being part of the Irish dance community is just that—it’s a community that is growing and evolving, changing as its influence spreads across the globe. You don’t have to be Irish to do Irish dance, but by entering the world of Irish dance you’re becoming a part of a living tradition that both honors the past while moving forward into the future. Through wigs, kilts, and beyond! This post is part of a series. Take a look at our last “Origins of Irish Dance” post, all about modern female costuming, here. Also: check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram.  The 1990s were all about going BIG The 1990s were all about going BIG The Look, Part 3: Modern Female Costuming Last week, we were able to make it into the 20th century, but this week we’re breaching the 21st with our discussion of Irish dance female costuming in the modern age! (Catch up on the history here and here.) For our purposes, the modern age of Irish dance is also the competitive age (though the tradition of feiseanna is, of course, a much, much older one!), starting with the establishment of the Irish Dance World Championships in 1970. The formation of this competition forced more rules and regulations into being regarding costuming and gathered together dancers from all over the world in one place—meaning trends were also able to take off. Even in the 1960s, a certain look had been established within Ireland and the trends of bouncy, curled hair (a long-ago Sunday church staple,) brightly colored dresses, and (eventually) deeply tanned legs (in a largely pale-skinned country) spread quickly.  The early 1900s versus the early 2000s The early 1900s versus the early 2000s But it wasn’t until the 90s that the current “look” of Irish dance really took off. Riverdance’s highly theatrical and flashy style not only brought Irish dance to the world’s attention, it also altered the Irish dance world. While Riverdance (the influence of which we’ll discuss more fully in another installment) actually didn’t use traditional Irish dance looks in the show, but rather took a more multi-cultural approach, the showmanship had its effects. Like much in the 90s, dresses got brighter and more sparkly, the wigs got bigger, and theatricality and pageantry became a part of the performance—as the sport grew in popularity, so did dancers’ needs to stand out among the competition. It would be hard to discuss modern, female costuming in Irish dance without bringing up its controversies. The use of fake tan—which is perhaps falling out of favor, but had been a staple of the competitive Irish dance circuit and Irish culture for decades—and makeup, as well as the often extraordinary cost of solo dresses and wigs has come under fire in recent years. Films and documentaries about other forms of dance, such as Cuties (which U.S. Netflix had to remove after an uproar from their audience,) have increased this outcry, while technology’s rapid advancements in the last two decades have left parents fearful their children aren’t given the chance to be children anymore. However, the first thing to note is this: “the look” of an Irish dancer isn’t compulsory, for the most part. Rules are even in place to discourage younger dancers from growing up too quickly--makeup isn’t allowed by the CLRG on dancers 10 or younger. Chances are your female dancer may be getting interested in makeup by 11 on their own—but even then, the heavy makeup used for competitions is part of the costume, necessary for judges to see a dancer’s face clearly under the hot performance lights, and part of all forms of performance for both genders as far back as records go. As far as fake tan goes, there’s no real reason for its prevalence beyond perhaps helping a dancer stand out and maybe look stronger, but natural looks have been have been coming back into fashion (and may go out in favor again—that’s what fads do!)  While still high on glitz, modern Irish dance solo dresses are a little less garish than their predecessors While still high on glitz, modern Irish dance solo dresses are a little less garish than their predecessors The main complaint from parents about many other forms of dance—oversexualization in dance moves—is one Irish dance steers clear away from. Irish dance’s steps may not be exactly what the Druids were doing around their bonfires, but they stem from quite literally ancient traditions and a deeply rooted and hard-won culture. There’s a gravity to Irish dance’s tradition and history that Irish dance’s costuming chooses to celebrate rather than cover up with the bright colors and many rhinestones, the tiara and bejeweled clips for capes and entry numbers (though there is a move to return to Celtic designs, like the more classic Tara brooch.) And while costuming throughout the dance world is also often (perhaps sometimes fairly) criticized, Irish dance’s costumes don’t fall under that category. Though the skirts may be short to better show the dancer’s only moving body parts, they’re generally very heavy fabrics, with long sleeves and often required to cover the collarbones, as well. Their expense is undeniable—though with the advent of computerized embroidery at home (among other innovations) and the continued increase of interest in the sport is helping to drive solo dress prices down—but they still cling to the roots of tradition with Celtic designs and influences. Irish dance, while loved worldwide, is still a somewhat insular community. However, it’s still a community! That means not every dress has to be brand new--the secondhand Irish dance solo dress market is a buzzing one! Last question I know is burning the tip of your tongue: why the wigs? The answer is simple: it’s easier and more restful than sleeping in rollers! Curled hair was synonymous with “dressed up” in Ireland for many years, and the bouncy curls as part of a dancer’s look has a far longer tradition than anything else they're wearing! Eventually, dancers simply got sick of being uncomfortable the night before a big competition, and switched over the wigs instead—which allowed for bigger and bigger hair. While styles have transitioned into lighter, curled buns and shorter, less heavy, curled wigs, it’s again part of the theatrical look and doesn’t seem to be going anywhere anytime soon! Don’t worry, boys, we didn’t forget about you! Tune in next week for the last part of our Irish dance costuming series: all about the evolution of the male dancer’s costumes throughout the ages. This post is part of a series. Take a look at our last “Origins of Irish Dance” post, all about both male and female hard and soft shoes, here. Also: check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram. Welcome back to our series all about the evolution of Irish dance costuming! While we’ll cover the sparkly dresses Irish dance is known for next week, this week is all about the most important aspect of any Irish dancer’s performance: the feet! (Or, more specifically, the shoes!) Before the mainstream introduction of ghillies (Irish dance lace-up soft shoes) in the 1920s, most woman danced barefoot or in whatever shoes they normally wore. But the precursor to modern ghillies is much, much older than that! Inhabitants of the Aran Islands in Co. Galway have always been master craftsman, and are the original inventors of the first version of the ghillies we know today. For thousands of years, Aran Islanders made and wore shoes made of a single piece of untanned leather, which was then gathered around the toes and cinched close to the foot with laces crossed up the top of the shoes (see image—looks familiar, doesn’t it?) These shoes were coined “pampooties” sometime in the 16th century (though Irish oral history means it’s unclear if the term was new or not,) and they were known for their flexibility. While untanned leather would generally stiffen up on its own, the fishing villages on the island and Ireland’s generally damp climate allowed the shoes to stay flexible. However, without proper treatments to preserve the leather, pampooties were only usable for about a month before the shoe simply rotted away.  The weight of those nails really adds up! The weight of those nails really adds up! It’s unclear how pampooties became the more modern, treated version of ghillies (it’s also the origin of Scottish Highland dance shoes, also known as ghillies, but with some small differences,) but today the shoes are made of supple, black kid leather made to mold to the dancer’s foot over time. The laces are much longer, with loops of leather to lace all the way up the top of the foot, around the arch, and then tied around the ankle. In modern Irish dance, only female dancers wear the shoes we know as ghillies, while men’s soft shoes have a construction more similar to modern jazz shoes—but with a special addition! Men’s soft shoes are called reel shoes include a raised heel with “clicks”—fiberglass heels the dancers are able to utilize to create precise sounds (which means different choreography than female soft shoes dances!) Conversely, the earliest version of hard shoes (otherwise known as heavy shoes or jig shoes) were, well, regular shoes! Dancers wore their everyday boots and brogues to dance for years, but they were always adding modifications to increase the volume of their steps. Irish dance has always been inextricably tied to music and the quick rhythm of the steps is what makes it unique—so making the shoes louder when they strike the floor has always been desirable. Originally, this effect was achieved by hammering tons of nails into the sole of the shoe, and making hardened, raised heels by stacking many layers of stiff leather together. As I’m sure you can guess, the shoes were indeed loud, but also incredibly heavy!  Modern Irish dance ghillies, with a pair of modern, fiberglass hard shoes at the end Modern Irish dance ghillies, with a pair of modern, fiberglass hard shoes at the end It wasn’t until the 1980s that the world of Irish dance embraced new methods for creating hard shoes. Even though fiberglass was invented in early 1930s, it took most of a century for Irish dace shoe makers to embrace it and figure out how to use it to create a lighter, more durable shoe. This invention allowed Irish dance to continue to progress into the 21st century, as the lightness of the shoe allowed for leaps and bounds (pun intended) in the types of choreography dancers are able to perform! Without all those nails and stiff leather weighing them down, Irish dance was able to take its place on the world stage and move from cultural dance form to the highly athletic and artistic sport it is today! Next week we’ll continue on into the 21st century and learn about how the image of an Irish dancer we know today came into being from these origins! This post is part of a series. Take a look at our last "Origins of Irish Dance" post, all about the history of female costuming, here. Also: check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram.  An Irish dancer performing in 1904 in her “Sunday Best” An Irish dancer performing in 1904 in her “Sunday Best” The Look, Part 1: Female Costuming History For many people, all they know of Irish dance is one thing: what a female, competitive soloist looks like. Big, curled hair, lots of makeup, maybe some fake tan on the legs, and, above all: a short, elaborate, bedazzled dress like nothing else in the dance world (or outside of it!) Like anything that’s such a consistent part of our cultural consciousness, we don’t necessarily think to ask the question: why? Why and how did the look we know today for Irish dancers come to be? With Ireland’s tradition of oral history, we don’t know quite how far back the tradition of Irish culture festivals (singular: feis (fesh) or plural: feiseanna) truly goes, but once the records start in the late 19th century, one thing is clear: there were no rhinestones involved. Feiseanna were a celebration of Irish culture, and Irish dancers didn’t have a particular look except that everyone always came in their Sunday best—generally ankle-length dresses, often white, lace-up boots, and with bouncy, curled hair to look their best—sometimes fashioning flowers or crosses made of ribbon to add decoration. However, the dancers eventually wanted their costumes to reflect their culture too!  Claire Kennedy, wife of the former Irish Attorney General, in Celtic Revival costume Claire Kennedy, wife of the former Irish Attorney General, in Celtic Revival costume Lasting from about 1885 until the 1930s, the Celtic Revival spread Irish culture not just across Ireland, but internationally, particularly in the production of textiles and ornamental brooches with designs dating back to the 1500s. During this time period, Irish dancers favored handmade, crocheted lace, handcrafted embroidered items in Celtic patterns, as well as pins with elaborate Celtic knots and scrolls that we still see on dancers today (often holding their competitor’s number!)  Peggy O’Neil in 1940—note the apron with her many winning medals, which were only worn for photographs Peggy O’Neil in 1940—note the apron with her many winning medals, which were only worn for photographs In the 1930s, with the forming of the CLRG (the main governing body of Irish dance to this day,) we started solidifying the concept of “costuming” within the Irish dance world. 8th century designs began to be favored, with reproductions of early Irish dress a precursor of what’s still Irish dance costume today, including a long tunic with dramatic sleeves (a leine) and a cape (a brat,) as well as handmade lace collars and cuffs. These items were often wrought of handwoven tweed and other handmade fabrics and designs that took inspiration from the famed Book of Kells and ancient, stone Celtic crosses and monuments. Skirts also began to creep up to the knee during this time period to better allow the dancers’ feet to be seen.  Vintage school costumes via @once_upon_a_feis on Instagram. Note the lace collars and cuffs! Vintage school costumes via @once_upon_a_feis on Instagram. Note the lace collars and cuffs! With the rise of Irish dance schools across Ireland and America (among other countries) in the 1940s, these costumes began to split the difference between historic and modern, transforming into something representative of the school and the Irish tradition behind the art. Touring companies of Irish dancers drew crowds in American cities who were nostalgic for their homes, as the costuming reminded them of historic peasant dress or Celtic artwork. Schools began to dress their dancers in matching school costumes and colors, favoring Kelly green, white, and gold most heavily. Until the modern era, red was considered too English and most schools didn’t utilize it (making SRL’s colors all the more distinctive now!) Tune in next week for a look at the evolution of most important part of any Irish dancer’s look: the shoes! This post is part of a series. Take a look at our last "Origins of Irish Dance" post, all about levels and competitions, here. Also: check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram.  SRL dancers in their school skirts at the 2019 New England Oireachtas SRL dancers in their school skirts at the 2019 New England Oireachtas Levels and Competitions, Part 3 Many of our parents and dancers here at SRL are fully aware of all the ins and outs of Irish dance, and this post isn’t really for them (unless they’ve always been a little fuzzy on some of it—we won’t tell! It’s complicated!) This post is for our up and coming dancers who are excited about competing more regularly. If you’re a Beginner, still learning the ropes, or checking out our website for the first time, check out the six previous posts in the series to catch you up to the present in Irish dance’s history! Regional Oireachtas to Worlds Irish dance’s prevalence these days isn’t simply a case of respect for the intricate footwork, perfect balance, and incredible stamina and grace it takes to make an Irish dancer, it’s a type of cultural exchange that expands the diaspora of the Irish people. Whether you’re of Irish heritage or not, participating in or watching Irish dance brings you a little closer to a country with a complex and rich history. It’s no surprise that the CLRG (the main governing body of Irish dance, based in Ireland) now have records to indicate “that Irish dancing is practiced in countries as far afield as Japan, Brazil, Argentina, South Africa and at an ever-growing rate in Eastern Europe.” Not to mention North America! In our previous two installments, we discussed the foundation of competitive Irish dance: the role of feiseanna (pronounced fesh-anna, the plural of feis i.e. fesh) and the different types of dances performed at these festival competitions (with corresponding music and at varying levels as your technique and skill develop.) But feiseanna are only the local level of the competitive Irish dance circuit. The next step? Time to move up to an Oireachtas competition! (At your teachers’ and parents’ discretion, of course!) The term “Oireachtas” (pronounced o-rock-tus, but say it quickly!) denotes a regional competition (as opposed to a local feis) that can be as broad as a whole section of the country, though the way your day goes will look much like a feis. Fun fact: as the word oireachtas roughly translates to “gathering” or “assembly,” it’s also used as the title of the parliament of the Republic of Ireland, but anyone in the Irish dance world will know what you mean! Oireachtaisi (the plural!) all over the world may have once been more or less very large feiseanna, but these days the annual competitions are held as qualifiers for the World Championship competitions.  The first World Champs in 1970! The first World Champs in 1970! In North America, there are seven regional oireachtaisi competitions each year (held in and around November) put on by the regional branches of the Irish Dance Teachers’ Association of North America (IDTANA.) Each regional (ours is New England!) oireachtas holds a main championship, which SRL dancers are able to start competing in once they reach the Preliminary Championship level. Somewhere in between Oireachtas and Worlds are national competitions (North America’s is usually in July) that are generally secondary qualifiers for Worlds and open only to the highest level of SRL competitor: Open Championship dancers (see more about the levels in last week’s post!) Depending on the size, these competitions can last several days. Each region also holds team competitions, where dancers compete together in groups of 4, 8, or 16 in traditional céilí dances. SRL dancers are invited to the team program when they reach Beginner II and have shown dedication to their dancing through consistent attendance and regular home practice. The céilí dances are standardized by CLRG and are a great exercise in dancing in unison while keeping impeccable technique, all by depicting beautiful movement patterns with those on their team! Regional Oireachtaisi may also hold a subsidiary competition for up and coming dancers to gain experience on the bigger stage. In New England, we hold a traditional set competition where dancers prepare one of the seven standardized traditional set dances to perform for three adjudicators. Once they complete this hard shoe choreography (that’s been passed down generation to generation!), the dancers receive a rank or placement based on rhythm, timing, technique, and posture. At SRL, dancers in the Beginner II Hard Shoe classes are invited once they’ve mastered the set dance “St. Patrick’s Day.”  A competitor and adjudicators at 2018’s Worlds—slight changes in 48 years! A competitor and adjudicators at 2018’s Worlds—slight changes in 48 years! 2020 held a number of unique challenges and disappointments, and none more devastating in the realm of Irish dance as the cancellation of the Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne’s (or the World Irish Dancing Championships’) 50th anniversary this past year. While there’s technically no less than six other organizations that call their competition “Worlds,” the Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne overseen by the CLRG is the oldest running (fingers crossed for 2021!) and often referred to as the “Olympics of Irish Dance.” It’s considered by many to be the most prestigious competition available for Irish dancers, and in its early days (1975) was won by no other than Michael Flatley (yes, the “Lord of the Dance,” aka the first name the average person knows in connection with Irish dance and the first American to win!) The first Worlds took place in 1970 (see the pic above!) in Dublin’s tiny Coláiste Mhuire theater in Parnell Square and to this day is usually held over Easter week. The competition remained in Ireland (though the towns and cities rotated) until 2009, when America hosted the competition in Philadelphia. (Though it has now been held in the other countries where the highest concentration of Irish dancers live: Northern Ireland, Scotland, Great Britain, and Canada.) And while Worlds may have started small, 2019’s event (hosted in Greensboro, NC) boasted approximately 5,000 competitors and about 20,000 supporters. When you think of the fact that upon its founding in 1932, the CLRG counted only 32 teachers and 27 adjudicators (aka judges,) it’s easy to see that Irish dance really has become a worldwide phenomenon! While this “olympic” event can be, in many ways, the pinnacle of an Irish dancer’s career (just qualifying is a huge achievement!) there’s many avenues for dancers to keep their love of Irish dance alive after they retire from the competitive circuit. Beyond the numerous professional companies that tour around the world, helping Irish dance, music, and culture reach innumerable people, many Irish dancers become Irish dancer teachers (just look at our staff!) or open their own studios (like Miss Courtney!) There’s also degrees (both BA and MA) in Irish Dance Studies (once again—Miss Courtney’s a great example,) though many dancers pivot into dance-adjacent professions: nutrition, physical therapy, arts administration or fundraising (to name only a few)…it doesn’t have to become a hobby in a dancer’s adult life! This post is part of a series. Read Part 1 of Levels and Competitions here and Part 2 here. Check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram.  SRL dancers on stage at the New England Regionals in January 2020 SRL dancers on stage at the New England Regionals in January 2020 Levels and Competitions, Part 2 Many of our parents and dancers here at SRL are fully aware of all the ins and outs of Irish dance, and this post isn’t really for them (unless they’ve always been a little fuzzy on some of it—we won’t tell! It’s complicated!) This post is for our Beginner parents, our dancers just getting excited about maybe competing, or even the parent just checking out our website for the first time. (If that’s you, maybe check out our five previous posts in the series to catch you up to the present in Irish dance’s history!) Leveling Up Note: the following is a general overview and varies by region—this guide is for our region, New England, USA. Your dancer’s instructor is always the best authority on any and all information pertaining to the competitive track in your area and your dancer’s level, specifically. Competition level names and our class level names may share similar terms, but are not directly related. There’s a quote written on the mirror in the larger studio here at SRL: “You earn your medals in class, you pick them up at competition.” Today, we’re going to lay out how the levels work on the Irish dance competitive circuit, but these levels aren’t about the shiny dresses and big hair—they’re about the discipline, hard work, and practice, practice, practice. The CLRG says it best: The purpose…is to provide a structured framework within which dancers can progress towards an achievable goal. [It] provide[s] a strong foundation in Irish Dance by developing a candidate’s physical skills, stamina, expression, musicality and an appreciation and knowledge of the traditional dances and culture. But, the competition must go on! To explain this all in the most basic way: competing and placing in a feis (check out Part 1 if this term is new to you!) is how dancers move up from one level to another. But the rules and regulations involving that movement are anything but simple.  SRL dancers with Director, Courtney, and Instructor, Christian, at a regional competition in January 2020 SRL dancers with Director, Courtney, and Instructor, Christian, at a regional competition in January 2020 Let’s take a closer look at the lower and intermediate levels, usually called “grades”: Beginner Grade: This level is for dancers ages 6+ that are brand new to competing for their first calendar year in the competitive circuit. Once a dancer has learned the necessary skills and steps at class—two steps of reel and light jig—they are eligible to take part in their first feis at the Beginner level. It’s always exciting to get on stage with the possibility of earning a medal for their hard work in class! Advanced Beginner Grade: Students remain at this level until they place 1st, 2nd, or 3rd in a competition of at least 5 competitors. They move up when competing in the next calendar year and only within the type of dance they placed in—i.e. a dancer can be a Novice in the Slip Jig, but still an Advanced Beginner in the Reel. You are not considered in the next level fully until you move up in all your dances. Novice Grade: This is the level where things begin to get more complicated—the steps get more difficult, and the tempo of the music may be slowed in order to fit more and more advanced steps into the dancer’s performance. Novice dancers move up only if they place 1st in a competition of 5 or more dancers, though groupings of 20 or more dancers will move 1st and 2nd place up to the next level in that specific dance. This is the level where solo costumes (as opposed to your school’s costume) are allowed.  SRL dancers of Novice Grade and above in their solo dresses in 2019 SRL dancers of Novice Grade and above in their solo dresses in 2019 Prizewinner Grade: An advanced level competitor that has placed fully out of Novice Grade, but is working on rising to the level of Preliminary Championship Grade. The regional minimum to advance requires a dancer to place 1st in both a hard shoe and soft shoe dance in order to move up, but, as the final grade before Championships, SRL dancers are required to win all their Prizewinner dances in order to advance. Now, let’s explore the championship levels, where the dancing is extremely advanced and dancers begin to compete at the regional, national, and international levels: Preliminary Championship: Competitors at this level generally perform three dances: soft shoe, hard shoe, and a set dance. At the championship levels, the soft and hard shoe dances get longer than they were in the grade level—this requires more stamina and strength. At Preliminary Championship level dancers are invited to represent SRL at the regional championships held each November. A dancer must win 1st place twice in order to advance to the top level of Irish dancing—Open Championship—and qualify for Nationals. Open Championship: The highest competitive level. Similar to the prelim level, dancers perform a longer soft shoe dance and a longer hard shoe dance, along with a set dance. Set dances are a dancer’s solo piece that showcases their best strengths, impeccable rhythm, and musicality. If a dancer wins a 1st at this level, they may never return to competing in Prelim. Open Championship dancers are pursuing high placements at regional and national championships and working to qualify for the world championships (often competing at major championships--The All-Irelands, The All-Scotlands, The Great Britains, etc.—though this past year saw the cancellation of many.)  An SRL dancer qualifying for Worlds in 2019! An SRL dancer qualifying for Worlds in 2019! While most Irish dancers start young and finish their competitive careers by their early twenties, many feiseanna offer competitions for older age ranges, as well! SRL offers recreational adult classes in six-week night sessions—perfect for dipping your toe in the Irish dance world! Feiseanna are competitive, but they’re also a cultural touchstone—bringing together people of every walk of life to celebrate painstakingly developed skills that bring alive Ireland’s vibrant history and culture. This post is part of a series. Read Part 1 of Levels and Competitions here. Check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram.  Vintage feis photos courtesy of @once_upon_a_feis on Instagram Vintage feis photos courtesy of @once_upon_a_feis on Instagram Levels and Competitions, Part 1 Many of our parents and dancers here at SRL are fully aware of all the ins and outs of Irish dance, and this post isn’t really for them (unless they’ve always been a little fuzzy on some of it—we won’t tell! It’s complicated!) This post is for our Beginner parents, our dancers just getting excited about maybe competing one day, or even the parent just browsing out our website for the first time. (If that’s you, check out our four previous posts here to catch you up to the present in Irish dance’s history!) A little recap: It was the Gaelic revival in the late 19th century, and the forming of the Conradh na Gaeilge (Gaelic League) in 1893, that helped Irish dance truly begin its journey from unrecorded folk tradition to the international, competitive art form it is today. With the League’s creation of a governing body specific to dance in the 1930s (Coimisiún Le Rincí Gaelacha—aka The Irish Dancing Commission or CLRG—still the primary governing body of Irish dance today,) Irish Dance Masters became a legitimate authority on a world stage (no pun intended.) The world of Irish dance as we know it today was built on this bedrock: the CLRG set down a series of rules and regulations to govern and standardize Irish dance (everything from steps and form to certifications for teachers.) This led to the creation of competitive opportunities to elevate its reputation, preserve and promote Irish culture, and nurture the art. And those competitions, rules, and regulations are what we’re here to discuss with you today! Feis Out the Best We’ve discussed feis and feiseanna (pronounced fesh and fesh-anna) before in this series—meaning simply “festival(s)”—they’re a long-standing tradition meant to celebrate and preserve Irish culture. Feiseanna today are still much the same (though in the dance world, they may only be a dance competition and not have as many outside vendors,) and vary in size: dance academies often hold inter-school class feiseanna, but there are also larger, regional feiseanna all over the world. These competitions are divided by both age and skill level (discussed next week!) and competitors are judged on a variety of technical and stylistic concerns such as timing, turn out, foot placement, deportment, choreography, rhythm…the list could fill this entire post.  @once_upon_a_feis @once_upon_a_feis To put this all as simply as possible: dancers compete in multiple different dances divided into two major categories: hard shoe and soft shoe. From those larger categories, more specific ones emerge based on the music and its timing, in three broad categories: jig, reel, and hornpipe (though the slip jig is completely unique in Irish music and dance with a 9/8 time signature—we’ll explain further below!) Soft shoe dances include the reel, the light jig, the slip jig, and the single or hop jig, while hard shoe dances include the treble or double jig, hornpipe, and treble reel. Most feiseanna will have dancers beyond the earliest levels compete in soft shoe rounds, hard shoe rounds, and then a final round that’s often hard shoe, and often a set dance (more about that below.) Some feiseanna will include team or cèili (pronounced kay-lee) dances, as well. But how does a dancer get to be a competitor? Dancers begin preparing for competition at the earliest levels: every move they learn in their Beginner later becomes part of a dance. Beginners start with the basic reel and jig. Once a dancer has mastered these basic steps and has good control of their technique, they begin learning hard shoe with the treble jig (essentially a hard shoe version of the jig they’ve already mastered and know the music for—but with hard shoe skills and movements instead!) Hornpipe and traditional set dances are added as a dancer progresses in their hard shoe technique. Each dancer will gradually add more complexity to these basic dances, differing in rhythm and timing, as they develop as dancers—for example: over time, the basic steps of the reel, light jig, and slip jig are upgraded with more difficult choreography. Traditional set dances are unique, tune-specific dances that were choreographed long ago by Dance Masters in Ireland to exactly match the music. They have titles such as “St. Patrick’s Day,” or “Garden of Daisies,” and are largely universal around the world (though there are slight regional and studio variations.) This is different to other types of dances (reel, jig, slip jig, treble jig, and hornpipe) that are unique to each school. This is why (well, at least until 2020 forced many competitions online) videotaping Irish dance competitions has always been forbidden—you have to protect that choreography!  What the layperson needs to understand in order to hear the differences in dances/music really comes down to is the timing: different dances have differences in their beats per bar of music, as well as different emphasized beats. Here’s a little breakdown of the major groupings, though further designations into dances have even further and more complicated variations (check out a musical theory breakdown of each one here and click on each type of music to hear an example!): Reels: 4/4 time signature and will probably sound the most “normal” to a non-dancer as the beats are evenly emphasized. Can be detected if you can say “double decker, double decker” in time with the music. Jigs: 6/8 time signature, i.e. three beats per bar with the 1 and 3 emphasized (non-Irish dancers will recognized this as a waltz.) Detected by non-dancers by saying “carrots and cabbages, carrots and cabbages” in time to the music. Includes light jigs and treble jigs, but not slip jigs! Slip Jigs: 9/8 time signature, i.e. similar to the above jig but with three beats per bar and three eight notes in one beat (with the emphasis on the 5 and 9 beats.) This one can give a lot of dancers some difficulties at first—it has an almost rolling sound to it! Hornpipes: 4/4 time signature, like the reel, but with the 1 and 3 beats emphasized. There’s more variation here, but many hornpipes can be detected with “humpty-dumpty, humpty-dumpty.” Next week, tune in to the blog for the purpose of feiseanna competitions (besides fun!): rising through the levels or “grades.” This post is part of a series. Read more about how Irish dance's iconic form developed here. Check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram. The Form If you had to ask someone who’s only seen competitive Irish dance once or twice in their life to describe it, the first things they mention are always going to be the same: 1) the footwork, 2) the distinctly rigid upper body, and 3) no arm movements. For the layman (or woman,) this is what makes Irish dance so clearly Irish dance when they compare it to other styles they’re familiar with. It’s not quite ballet or jazz or tap, but something unique and artful on its own terms…and it’s the lack of movement in the upper body that seem to distinguish it most clearly. This brings us to the question that people have been asking for at least the last 100 years: how did Irish dance end up with such a disparate and distinguishing form? What swirls around out there are plenty of rumors and hearsay—myths and stories. But what can we know for sure? The first issue with determining the form’s origins is that of Ireland’s oral tradition. Until the 1800s, we have very few recorded texts or notations of any dances that were performed. If you read the first three volumes (I, II, III) of this series, you know we only have the vaguest outline of Irish dance’s history, and what we do have speaks of bans, restrictions, and a variety of foreign influences over the years. The rumors that abound can’t be confirmed or denied and largely concentrate on the English suppression of the Irish and the constant religious upheavals that have plagued Ireland for centuries. One story tells of the Irish dancers who were brought to England to perform for Queen Elizabeth I: they refused to raise their arms to the foreign queen and the concept caught on. Another tale tells us that the Irish would dance behind bars and hedges to hide their practice of Irish culture from the Anglican church in the 18th and 19th centuries—the only part the authorities could see was their torsos, so they learned to keep them still. This one seems even more unlikely (maybe they wouldn’t have seen their feet, but I think I’d notice a bartender hopping up and down,) but the time of hedge schools and religious oppression were very real. The speculation doesn’t stop there, but it all revolves around a similar theme: oppression and defiance. It could be English soldiers tied the Irish up and made them dance, or that the Catholic church restricted the arm movements to make the dancing less provocative. Or maybe it’s just that Irish pubs are so crowded, you can’t move your arms! All these ideas seem to tell us more about the Irish love of storytelling than their dance traditions. What seems more likely from a historical standpoint is a combination of two factors: the influence of French court etiquette and decisions made as Irish dance became a competitive and international art form. The Dance Masters of the 18th and 19th centuries were also known for their concentration on decorum, having been trained by the (supposedly) more refined French. In hopes of taming the “wild Irish,” arm movements were removed to help civilize them. But this could still just be gossip. What we know for sure is that when the Gaelic League (“Conradh na Gaeilge”) was formed in 1893, and then the Irish Dancing Commission (“An Coimisiún Le Rincí Gaelacha”) in 1927, the two organizations decided on specific criteria for Irish dance that has mostly remained till this day. Though there’s some controversy in modern circles about the Irish Dancing Commission’s decisions to standardize Irish dance, it was considered helpful from the perspective of judging to have the arms uninvolved so there’s no distractions from the feet. In any case, this is the only real, recorded evidence we have available to us for a specific reason Irish dance developed such a unique form.

While competitive Irish dance still adheres to this rigid posture, there’s of course traditions and performances that break from this standard (most notably Sean Nós, céilí dancing, and modern interpretations of step dancing like Riverdance—something we’ll cover in another post!) However it came to be, the form that was once a symbol of oppression is now one of defiant skill. After all, Irish dance’s form has added another difficult element to a dance style already known for its rapid and complex footwork—no other dance style expects perfect balance without the help of the arms! This is Volume IV of a series. Read Volume III about Dance Masters and Gaelic Clubs here. Check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram. Dance Masters and Gaelic Leagues The next chapter in the saga of Irish dance through the ages will look a little more familiar to our SRL families: the Dance Master. A precursor to the TCRG (like Miss Courtney,) Dance Masters were a flamboyant fixture in 1700s Ireland known for their itinerant lifestyle, brightly colored clothing, and the staffs they carried. Dance Masters traveled Irish districts in search of a pleasing town to stop in, and more importantly: students to teach. It was considered a great honor to have a Dance Master stop in your town, and a greater honor to house and feed them when they came to teach. The dances they taught were heavily influenced by the set quadrilles popular in the French upper classes, and the Dance Masters were considered extremely cultured and civilized due to the emphasis they placed on proper manners and deportment. This clashes directly with the setting: most of these classes occurred in barns and many students didn’t know their right from left. To combat this issue, Dance Masters would tie hay or straw to one of each student’s feet and ask them to “lift hay foot” or “lift straw foot”! While the Dance Masters were all about French etiquette and dancing (precursors to the sets students still learn today,) they also had some adventures along the way. Sometimes Dance Masters were kidnapped (playfully, we assume) by neighboring towns who wanted lessons. Dance Masters also often competed against Dance Masters from neighboring districts at céilís or feiseanna—large gatherings celebrating Irish culture and traditions usually held at a crossroads at the time--reportedly until one of them dropped! Since the Statute of Kilkenny (check out Volume II for more details,) Irish culture had been contained to the Irish (in law if not in practice,) and still felt somewhat oppressed by their English neighbors. The forming of Conradh na Gaeilge (The Gaelic League) in 1893 changed everything by establishing an organization specifically dedicated to preserving Irish language, literature, folklore, music, dress, and, to a lesser extent, dance. While the League originally outlawed certain dances that weren’t considered completely Irish (like the set quadrilles so heavily influenced by the French,) they eventually rescinded their stance. In 1930, An Coimisiún Le Rincí Gaelacha (The Irish Dancing Commission) was formed to preserve and promote all forms of Irish dance and still exists to this day.

In 1897, the first public céilí was held in London (perhaps not so ironically, when you consider the goal of preserving Irish culture for all Irish people—there was a fair amount living there.) After the Commission was established only a few decades later, it only took a few years for their work to spread to wherever Irish people lived—which by then was everywhere! Now, there are Gaelic Leagues and Clubs all over the world and feiseanna are held wherever they are. Irish dance comes from a tradition that resembles the American dream as much as anything Irish: a melting pot (doing my best to refrain from a pot o’ gold pun) of traditions and cultures. While it honors a specific heritage wherever it’s performed, that heritage was created over millennia through a distinct and unique combination of different people and civilizations. At SRL, as we’re proud to continue that tradition by keeping to the heart of it: honoring Irish culture, while always remembering you don’t need to be Irish to do Irish dance! This is Volume II of a series. Catch up with Volume I here and Volume II here. And check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram. The Statue of Kilkenny and English Monarchs Just as the history of Ireland is rife with conflict, so is the history of Irish dance. It might sound dramatic (or a little bit too much like Footloose,) but there was a time in Ireland when Irish dance was essentially banned. Well…not for everyone. In the 14th century, the English began to feel they were losing the foothold on Irish soil they had gained in 1177 through a pact with the Normans (for more about them, see Volume I!) Scrambling, they took action by enacting the Statute of Kilkenny in 1366—35 laws banning anyone except the native Irish from partaking in Irish traditions. Among the many banned activities within the Anglo-Norman settlement were: riding horses “Irish style” (i.e. without a saddle,) listening to Irish storytellers, wearing an “Irish beard” (whatever that means,) marrying an Irish person, utilizing any Irish names or dress, and even playing any Irish games or music. While these laws didn’t expressly forbid Irish dance in so many words, the intent was clear: Irish culture (including dance) was only for the native Irish. However, you can’t keep a dancer from dancing. The fears of the English—so close but so far away without modern air travel—had come true: their settlers had become “more Irish than the Irish themselves.” In fact, these laws were so loosely enforced that they weren’t technically repealed until 1983! Besides, it wasn’t long before those back in England began to change their tune once they saw all that impressive footwork in person. No less than Queen Elizabeth I herself became a fan of Irish dance when Sir Henry Sydney wrote to her of girls he saw dancing jigs in Galway in 1569: "They are very beautiful, magnificently dressed, and first class dancers." After receiving the letter, the Queen reportedly invited and hosted Irish dancers at court.

And Queen Elizabeth I wasn’t the only English royal who sang the praises of Irish dance. Historians have found evidence that one of her successors, James II, was greeted upon his arrival to Ireland in 1689 with Irish dancers (though the trip didn’t go so well for him after that welcome.) These were the first steps (pardon the pun) of acceptance for Irish dance that has let the tradition travel beyond Ireland’s borders to become the worldwide celebrated art form it is today. This is Volume II of a series. Read Volume I here. Check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram. The Druids and the Normans There are many things in this vast world we don’t know the truth of: the Easter Island moai, the Nazca Lines, and even eels (hard to believe, but it’s true!) With legends reporting the earliest feis to have taken place three millennia ago, the beginnings of Irish dance fall into a similar category: a cultural marvel whose origin has been lost to time. (Okay, maybe eels are in a different category.) While there’s no definitive answer for who the original practitioner of Irish dance really was, historians do have some educated guesses. The Druids—a learned class in early Celtic culture that was a mix of priest, teacher, doctor, judge, and even warrior—are most often credited with the earliest version of the dances we practice today. The Druidic class was highly respected in ancient Irish culture, with the word “druid” thought to have come from the Irish-Gaelic word “doire,” meaning oak tree or wisdom. The biggest difference between modern Irish dance and Druidic performances? The Druids are believed to have danced as a form of worship. It’s thought that as early as 1600 B.C. the Druids were performing circular dances (possibly among standing stones, the most famous of which you may have heard of…Stonehenge) for a variety of reasons: to worship the sun and their namesake oak trees, as preparation for war, as a prayer for prosperity, as a courtship ritual, and even something closer to modern feis—social gathering and recreation. But the Celts had some company knocking at the door. Ireland was invaded by the Normans in 1169 A.D., a group of Viking descendants previously settled in what is now Northern France. With their forces, the Normans brought a variety of traditions with them, including “carolling”—which is essentially a mix of Druidic circle dances (which were already similar to early French tradition,) and the singing we associate with modern caroling around the holidays.

“Carolling” led to one of the earliest known mentions of Irish dance in writing in 1413, when the Mayor of Waterford visited the Mayor of Baltimore (we've borrowed many a town name from the Irish!) and was presented with a procession of singing and dancing. While modern Irish dance is a little too athletic to expect anyone to sing while dancing, the custom of combining traditional dance and music is still carried out at most Irish dance academies. That includes us here at SRL! This is part I of a series. Check out the blog every Monday and Thursday for more posts about Irish history, dance culture, community news, and spotlights on our dancers, staff, and families—among other fun projects! And don’t forget to dance along with us on both Facebook and Instagram. |

SRL NewsFind all of our latest news on our Scoil Rince Luimni Facebook page! Categories

All

Archives

August 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed